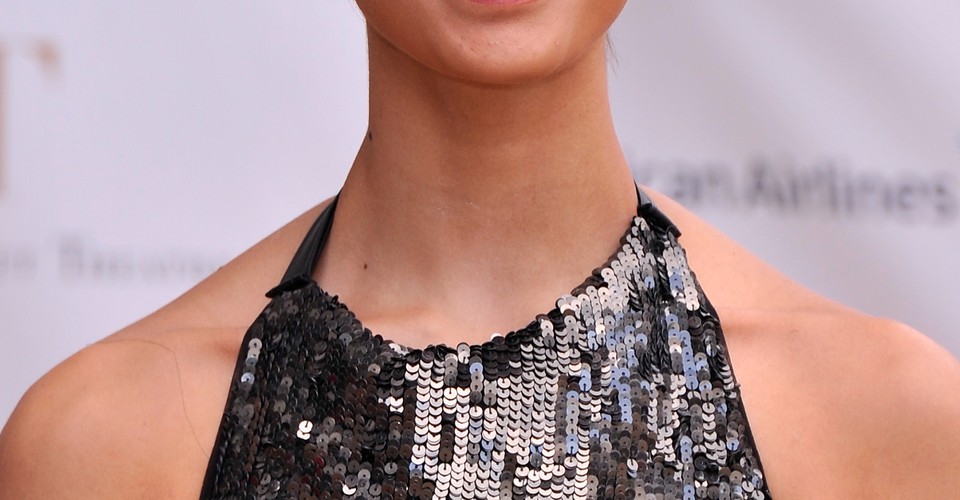

In 2007, Misty Copeland became one of classical ballet’s most recognizable figures when she secured a spot as the first black soloist in two decades to perform with American Ballet Theatre. Five years later, she continued to make history by becoming the first African-American woman to take on the title role in Igor Stravinsky’s iconic ballet, Fire Bird, for the classical ballet company. Not bad for a dancer from a single-parent family who put on her first pair of slippers at the overmature (for ballet) age of 13.

Earlier this month, Copeland released a memoir, Life in motion: an improbable ballerina, which details his childhood in San Pedro, Calif., as an anxious perfectionist who went from living in a motel with his mother and five siblings to sharing a stage at the Met with the best dancers in the world. Since she didn’t have the “traditional” experience of being a ballerina, Copeland says she had to learn to accept the advice of others on everything from healthy eating habits to living independently as a professional in New York City. that she was still a teenager.

Like many dancers, she experienced puberty late in life, more or less induced at age 19, and had to abruptly weigh the criticism of her mature, seemingly alien body against her rebellious instincts to eat and do what she wanted. wanted to. Later, since conditions such as stress fractures are among the most common pitfalls (career ending for up to 43% of dancers in the United States, according to a report by The Advance Project), Copeland must have been aware of her prospects after being sidelined by injury shortly after her debut as a Firebird. Now at a safer place in her career and still moving forward, Copeland spoke to me about the physical and psychological demands of being a top ballerina.

What’s your schedule now in the middle of the current American Ballet Theater touring season and your book tour?

Right now, ABT is gearing up to shoot in Abu Dhabi, so we’re in the studio from 10:15 a.m. to 7 p.m., five days a week, Tuesday through Saturday. It’s what I do every day and it’s my first job. During my free days, that is to say Sundays and Mondays, I go on reading tours. It was crazy.

In your book, you talk a lot about the physical demands of being a professional dancer, especially after discovering the stress fracture in your lower back a few years ago. In particular, you wrote: “An injury can be as painful psychologically as it is physically.” Can you talk a bit about the experience of being an injured dancer?

Ballet dancers are such a niche art form. So few people have what it takes to get to that level in elite companies because you really have to have the physical attributes and the strength, the ability to be an entertainer on stage, and the mental toughness as well. There are so many elements involved, but the psychological and the emotional are just as much a part of it. I was 29 when my last injury happened. As an old dancer, do you think, will this distract me for two years? Will I be able to come back from this in time to continue and become a principal dancer? Could this be the end of my career? You are constantly confronted with all these things. I’ve been through all of that, so I think it’s important for us to be around people who are going to keep us emotionally intact and on track.

To stay on track, what is life like in the pre- and post-pubescent world of dance? How does this inevitable physical change positively or negatively impact your work?

As a professional, that’s the scariest thing to experience – your body changes – because it’s your tool. It’s your instrument and when it’s unfamiliar to you, you don’t know how to use it. It was therefore extremely difficult to go through puberty and change my body at such an advanced age, 19, when I was already a professional. It took me years to listen to the words of others and accept advice on how to really treat it like the instrument it is, to learn.

Where does your resistance to accepting advice from others come from?

Being a teenager and not understanding that you can’t do this on your own. That was it. You want to make these decisions for yourself and sometimes you just can’t. You can find great mentors and later, when you’re older, companies offer bridging programs, but as a professional you’re really on your own; there is no structured guidance from the company. That’s why I try to have a voice and to express to our young people how to go about being a professional and diving into this so unfamiliar world.

In some ways, this discussion reminds me of the saying “youth is spoiled by the young” – is dance spoiled by the young? Do you think there is a peak time when dancers are best able to handle these physical and psychological impacts? You have this immense physical capacity when you are younger, and yet the maturity to handle this job comes with age.

To the right. There really is no way around it. You have to start very young, which is difficult because you are expected to become an artist with so little life experience. For me, I feel like I’m becoming the artist I want to be. It takes time, but I think older dancers are the best performers just because they have more experience and more life to draw from – but I’m still getting there and I’m still growing.

Do you think you have a different perspective on limitations like age because not only did you start later than most dancers, but as one of the few black dancers at your level, you just a different environment?

Absoutely. I think I’m proof that you don’t need to have all the things people think you need to have to be successful in this world. I think it’s possible to mold and shape a body into whatever you want to do, and whatever type of dance you want it to do. With the knowledge you have of your body, of work and of cross-training, I think it is possible to train to do everything.

The conversation about conventions in dance is a bit like the concerns people have with casting when it comes to turning books into movies. There’s a feeling that there’s a line in terms of what a dancer – and particularly a ballerina – should look like. How, if at all, has the ballet environment changed in terms of options for older dancers or dancers from different backgrounds since your debut?

We’re characters on stage and acting, so I don’t feel like there’s an ideal image you should have, like with actors and actresses. The goal is to have the ability and the talent to take on a character and take on something that you are not, and that’s what we do. In terms of body types in ballet, I think the field is becoming more open than before because of the types of movements and choreography that we do that call for us to be more athletic. We have to have muscles to support that, so I think the dancers look healthier now, and I hope we start a conversation about diversity to make changes.

When you remember your first meeting with the famous ballerina Raven Wilkinson and other black dancers who preceded you or became your contemporaries, you said it was significant to meet someone else who spoke “the same very rare language: that of a black classical ballet dancer”. Why were these great moments for you?

It’s heartwarming to meet someone who is a rarity in the world of classical ballet. I think as a young adult you are looking for a connection with people who can understand and relate to who you are as a person. I didn’t have that in the company initially; I was kind of thrown in there all by myself. So to meet someone like Raven who could understand all of those little nuances that you feel as a minority, and who can still speak that language of ballet and dance, was very meaningful.

There is another African American dancer in the company, Courtney Levine, who is the first black woman to be in the company with me. The first 10 years of my career, I was the only black woman in a company of 80 dancers, so having another black woman in the company and seeing how diverse the schools are, I think, are signs of growth and change in the field.

What is the biggest impediment and impediment to increasing the number of dancers in classical ballet?

I think that if [you don’t have access to classes] at a fairly young age, there’s no way to get the training you’ll need to compete with dancers from wealthy backgrounds. It’s about being exposed to classical ballet at a young age, which is what ABT’s Plié project does. In conjunction with the Boys & Girls Clubs of America, the program gives young people access to classical ballet at their local clubs and to teachers trained and certified in the American Ballet Theater program so they have an equal opportunity to become good enough to audition with other dancers.

What are the things you look forward to doing in the future? Do you intend to go beyond ballet?

I feel like I’ve done them all already, and more than I ever imagined. I’m signed with Under Armor and it’s amazing to be a performer alongside all these professional athletes; and I have a children’s book coming out, Bird of Fire, with Christopher Myer. But right now, I’m still trying to have my ballet career. I do my best to do fun outdoor things while staying true to my art. And I’ve been blessed with amazing opportunities outside of American Ballet Theater, but right now I’m totally focused on my commitment to the art form and the dance in this company.