Allynne Noelle and Thomas Brown opened WestMet Classical Training in Long Lake in September last year after a virtual run that several months earlier had started with semi-private lessons in their loft and a gradually building client base.

A new extension is underway this summer.

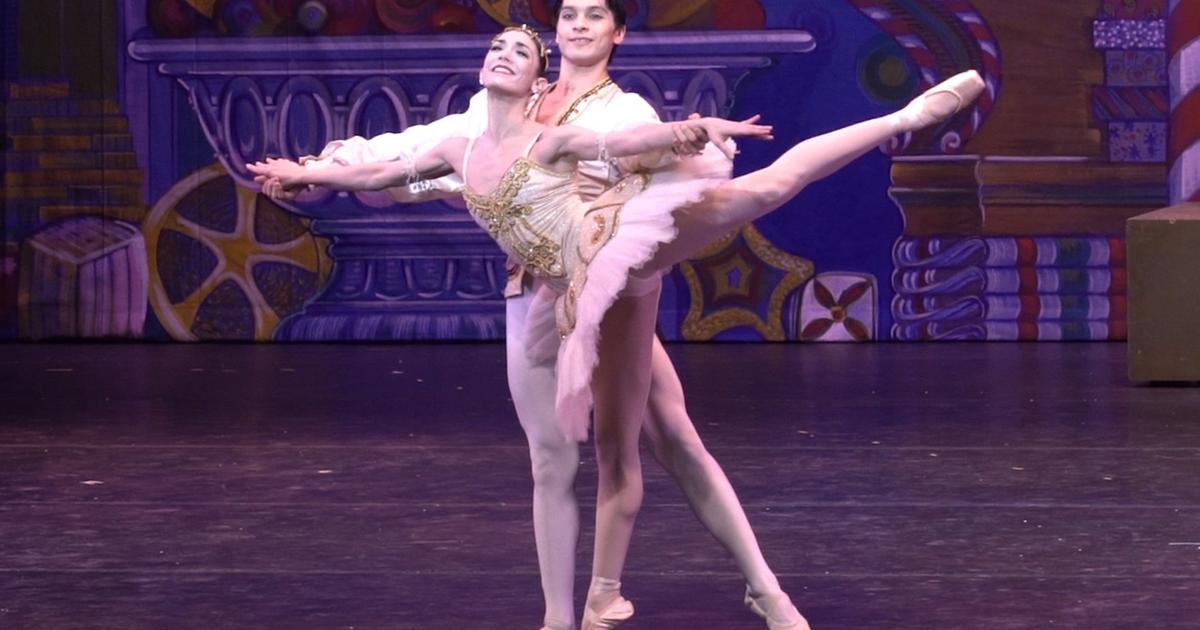

Noelle and Brown presented their first classical performances at the Westonka Performing Arts Center earlier last month in a series of repertoires that introduced their students to what Noelle and Brown know very well: what it is to dance on stage without be inhibited by the pressures of competition.

This separation of the art of score – performance from judgment, dancer from competitor – is what sets WestMet apart from day one.

“You either have to join the college dance team or that’s it – you pack your shoes, put them away, and you’re basically retired at 18.” The somewhat artificial cut-off from a beloved sport didn’t seem right, Noelle says, but it’s what often defines the competitive dance circuit – and many dancers don’t even know there are programs for it. pursue art in a professional manner.

Noelle, from Southern California, first donned her kindergarten dance shoes during an open house at her friend’s dance studio, first practicing in what she describes as the “pure and unaffected” style of Italian ceccetti and later specializing in Balanchine’s “more Americana style.” She signed her first professional contract at age 15 and, far from retiring three years later, made a career in the Los Angeles Classical, Miami City and Suzanne Farrell ballet companies.

Brown, from Jacksonville, Fla., Had a ballet teacher for a mother and a baseball coach for a father and says he fell into ballet when he noticed his sisters were warming up with stretches similar to the ones he used on the mound. He resisted the ribs of his friends – and pushed them to test their strength with ballet – and eventually signed with the Richmond Ballet Company, performing on stages at London’s Royal Opera House, Beijing’s Egg and of the Grand Shanghai Theater.

It may sound like a dreamer’s ambition, professional ballet, but that’s why Noelle and Brown made their studio what it is, they say.

The pre-professional program aims to fill what Noelle says is a “huge training gap” created by a hyper-focus on technique that leaves little room for understanding the off-stage facets of a career in concert ballet. .

“You’re so muscle-trained when you’re a kid to learn that technique and master your body, then you get your job and you become a pro, and when you’re a pro you’re supposed to know all of that. things you haven’t been exposed to yet because so much emphasis has been placed on your instrument [body]. “

She and Brown train their students in a basic technique, malleable to the styles preferred by different companies. But they go beyond technique to also teach their dancers those aids that help turn art into a career: how to work in a body with other dancers, how to add to a repertoire, how to keep the body in a healthy sense and avoid injury … Noelle takes the count before adding that there is a lot of autonomy in professional ballet and that one can have the impression of “going up a stream without a paddle” if these tips are not the.

Despite their dismantling of the dreamer’s ambition into a down-to-earth game plan to achieve it, Noelle and Brown are also candid about the realities of concert ballet as a profession.

“There is definitely a shelf life,” says Noelle. Brown adds that the injury is not a question of “if” but “when”.

Ballet “works against your natural skeletal structure,” Noelle explains. “Everything is turned outwards, [and] you’re essentially deforming your muscles to wrap around your skeletal structure in a different way.

It is also make or break. “Either you have the discipline for it or you don’t,” says Brown. “It’s so precise. It’s in black and white. It is either good or bad.

Yet the industry has evolved and in a way that recognizes these risks.

“That ballet mentality of starving artists of the 1970s is kind of disappearing,” says Noelle, looking through the window of the studio where a course in variations ends. With dancers reaching their peak in their late teens and twenties, larger companies are now realizing that it is a more “human and realistic” approach to allowing their trainees to enter the dance hall. college and thus have an alternative in the event of retirement or injury, she said.

Noelle and Brown will often work as part of the Youth America Grand Prix, an international scholarship program and a major contribution to professional ballet programs. WestMet students, who dedicate 17 hours of lessons per week, as well as rehearsals and private lessons, have already secured internships at such sought-after locations as the John Cranko School in Stuttgart and the Princess Grace Academy in Monaco.

“They meet us halfway with their ethics and dynamism,” says Noelle, now standing again after putting on a pair of low-heeled character shoes: she’s leading the next class in 5 minutes. “Because we are not easy with them, for sure”

Noelle and Brown will then bring their students to the Westonka Performing Arts Center at the end of October for a collaboration with the PAC choir. Also on the program, a performance “The Nutcracker” in December and a return in June of the repertoire series. Check the PAC website for exact dates.