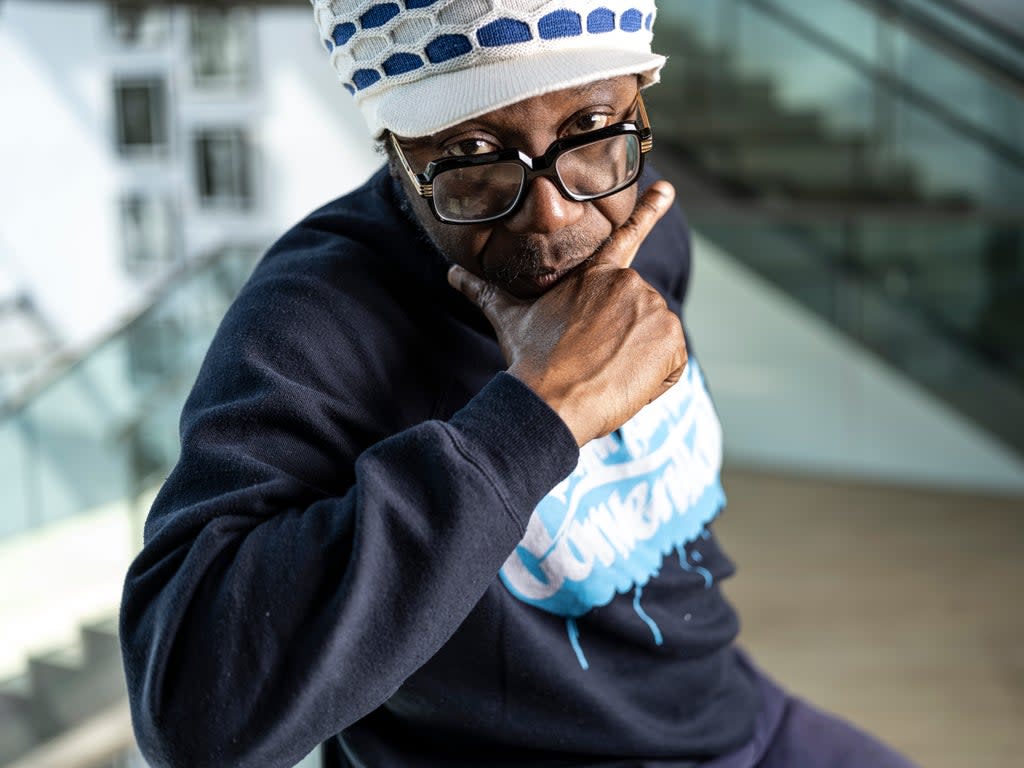

Is (whispered) break dancing losing its cool? Not if Jonzi D had anything to do with it. The MC, dancer, spoken word artist and director has long been credited as one of the founders of the UK hip hop scene, helping to bring the lockdown, popping and krumping from fringe interests to some of the biggest theaters in the world. world, bringing in a whole new audience. — not to mention the dance establishment — with him. Now, of course, b-boying is pretty much everywhere, from Britain’s Got Talent to Super Bowl halftime; in two years it will even make its Olympic debut as a sport at the Paris Games. And speaking to Jonzi, in the cavernous backstage of Sadler’s Wells theatre, where he created the groundbreaking Breakin’ Convention nearly two decades ago, it’s clear he’s surprised at how much this form of art has become ubiquitous.

“Hip hop is everywhere now. It’s the main cultural vehicle and I’m really surprised what happened with it, to be honest. I remember starting out thinking, “Look, all we want is a little time to do our thing in this big tableau of the theatre.” We’re not asking too much, we just want some funding to see if that’s a thing. Today, hip hop has become the norm. If you want to be in dance, if you want to be on the business side, on the artistic side, you have to understand the disciplines of hip hop. He smiles, sadly. “It’s pretty mind-blowing to me.”

Things were very different when he was a dance student in the late 1980s. And she said no – because we prepare students for the market, that’s why we were learning ballet, jazz and contemporary. At the time, we were looking at people like the Nicholas Brothers, the old school black jazz dancers, and I thought there was this whole new dance scene coming from these black parts of America, and why wouldn’t it? are we not studying? I just thought, ‘Okay, challenge accepted.’ My thing was to change the market by showing that these other forms of dance are also valid in a theatrical context.

Jonzi’s early experiments with what is now known as hip hop theater – notably in his Lyrikal Fearta (1995) and Airplane Man (1999) – immediately caught the attention of critics with their bold blend of poetry, music and movement. An invitation from Alistair Spalding, now artistic director and CEO of Sadler’s Wells, to hold a festival in Islington soon followed, although it took until 2004 for their dream to come true. Then, as now, Jonzi was determined that Breakin’ Convention capture the spirit of the original hip hop artists and their “values of peace, love, unity and fun”, showcasing the pyrotechnic brilliance of the art form, but ensuring its vehement political bent. didn’t miss either. This year’s three-day programme, which opens tomorrow, is a case in point: there are pieces from Peru’s D1 Dance Company, with 12 dancers exploring their lives in the barrios of Lima, as well as the team French Compagnie Niya, whose feature film Gueules Noires is a tribute to migrant workers in the Nord-Pas de Calais mining basin. There will also be a live performance of Our Bodies Back, first made as a choreo-poesic film by Jonzi during the pandemic about violence against black women. Unfortunately, the convention’s popular Ukrainian artist, contortionist Kate Luzan, will no longer be appearing. (“She’s still in Ukraine – she says she’s in a safe place, so… But next year she’ll be back.”)

Jonzi is also excited about his latest project: creating a hip-hop theater academy at the new Sadler’s Wells East in Stratford’s Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park. The school, due to open in 2024, will accommodate around 20-25 students aged 16-19, each graduating with an extended Level 3 diploma after two years of study. All places will be fully funded.

“I’m looking at it in the context of musical theatre, so they’ll be studying dance – the techniques of breaking, popping and modules in some of the other styles, for example krump, litefeet – but also rapping, singing, acting. There will also have some graffiti lessons. The fact is that all these forms are linked to each other and to the first generation of hip hoppers. In the early 1980s we were doing break, we were doing pop, we were doing a little bit of graffiti, but over time, each element of hip hop culture has spread and developed on its own: now breakers only break, rappers only rap. I want to bring all forms together.

While he wants everyone and anyone to apply, be warned: this is not a course for keen amateurs. “I really want to push these students physically. I have the impression that the teaching of dance has become a little soft. There is a bit of a nanny quality when it comes to basic training and in some schools – not to mention names – the standards have gone down. At this particular stage, we want to push the standard, so I want to work hard. I feel guilty saying that but I shouldn’t.

The creation of his own school of hip-hop also allowed him to confront one of the biggest bugbears he faced during his own dance training: namely the insistence that classical ballet is the root – and most important – of all dance forms. “It’s clearly not the truth – loads of dances are the root of their own dance,” he says with a grimace. “It is only a colonial state of mind that will allow this expression. “Oh, classical ballet, you have to learn classical ballet, then you can do everything else.” I remember being told that, but let’s also look at this: a highly skilled ballet dancer, have you seen them dance any other dances? It looks awful!”

It’s hip hop, he says, that holds the key, not only to expressing the “big ideas” in dance, but also to addressing diversity issues within the sector – an issue with which many dance companies have, until recently, struggled. “Hip hop presents you with really tough stuff that you have to deal with; it doesn’t make it easy for you. So I think hip hop is important when it comes to the development of new ideas and especially the development of diverse ideas. One of the concerns I’ve always had with these spaces” – he gestures around him – “and with classical ballet, is that a lot of what’s important [to it] comes from a tradition of the aristocracy, of Louis XIV and court dances and all that. Then it was about establishing a higher level of everything: how you walk, how you look down on people, shouldering as they call it. Such [of the artform] is wrapped up in, to some degree, colonial voices and I think it’s really hard for it to then become what is the vehicle for diversity… I just think our path to culture can’t be with this cover of oppression and when I walk in the Royal Ballet, I feel it. I don’t feel that when I’m in the Breakin’ Convention audience.

How does he think Sadler’s Wells – which mainly attracts a white, middle-class audience – will fare in east London, in the middle of one of London’s most ethnically diverse areas? Jonzi, who grew up a stone’s throw from Bow, feels nothing but excitement. “I feel like I’m bringing Sadler’s Wells home. I feel like it’s my fault, in a really positive way. It will be great for the area I grew up in. And I’m determined to make sure the local community doesn’t feel like it’s something that’s been parachuted in. Alistair [Spalding] gave me a lot of responsibility to build those bridges – and,” he smiles, “I’m all for it.

Breakin’ Convention is at Sadler’s Wells from tomorrow to Sunday; 020 7863 8000, sadlerswells.com