Recently, the first English National Ballet artist, Precious Adams, announced that she would no longer wear pink tights. With the support of her artistic director Tamara Rojo, she will instead wear chocolate brown tights (and shoes) to match her skin tone.

It might seem like a simple change, but it could be a watershed moment, a time when the aesthetic of ballet begins to expand to include the presence of people of color.

With all the work being done in the world to increase the number of black dancers in ballet, it was only a matter of time before we got here. Bare legs and flesh-colored shoes are commonplace in contemporary ballet, but in classical and neoclassical ballet, pink tights and shoes remain a mainstay.

Dance Theater of Harlem debuted in flesh-colored tights and shoes in 1974 on the last stop of a European tour. Dancer Llanchie Stevenson was the catalyst: from her early days in the business, she constantly implored Arthur Mitchell to allow them to wear tights and shoes to match their skin color. Stevenson explains, “One day I noticed my arms were a different color than my legs, I thought I looked so disjointed. I started wearing brown tights over my pink tights. Mitchell liked it so much that he decided that all dancers should wear tights that match their skin. The ruling was a declaration of ownership of the art form and a redefinition of classism.

Where does the tradition of pink tights come from? In the 1790s, Austrian ballet dancer Maria Viganó shocked Parisian audiences when she and her brother Salvatore performed in sheer white chiffon tunics, her legs covered in flesh-pink hosiery that gave the appearance of nudity. At the time, the Paris Opera banned “nude pink” for social reasons, but by the end of the 19th century, pink tights were the norm. The intention was to do away with both stockings and shoes, and at the time, pink was as close to nude as it could get without theaters being set on fire in a scandal.

Little thought has been given to this tradition since then, but it’s safe to say that the only reason ballet tights and shoes are pink is that by the time the tradition began, all dancers were white. As racial uniformity diminishes, shouldn’t we re-evaluate the suitability of pink tights and shoes? Couldn’t we say that the real “tradition” is that tights and shoes should match the dancer’s complexion?

Most of the arguments against flesh-colored tights center on preserving the classic aesthetic of uniformity. You could say that brown tights work for DTH as they are a group of colored dancers, so brown tights are in a uniform sense. But when there are only one or two dancers in the body wearing brown tights, some think it ‘breaks the line’.

This begs the question: What is the difference between a brown arm and head and a brown leg in line? Not a lot. But there are directors who still consider the noticeable browning in the body to be problematic.

In the mid-1980s, when Ben Stevenson of the Houston Ballet (not related to Llanchie) chose a promising Lauren Anderson in his ballet. Pair Gynt, it was the first time that her complexion was artistically discussed. “The suit was a unitard that went from flesh tone (white) to green, when I put it on it didn’t look right, so they dyed the legs to match my skin, and it was the first time it was done, “Anderson says. Stevenson was also open to her wearing her natural hair in the role as long as it was thematically tied.

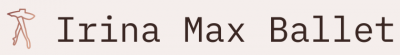

Later, during a Nutcracker rehearsal technique, Stevenson found that Anderson’s legs in pink tights like Sugarplum looked gray under the lights. They decided to experiment with a few shades of brown but none looked right. “Finally, Ben said, ‘Call the Dance Theater of Harlem and find out what they’re using.’ It was music to my ears, ”Anderson recalls.

Once she did Sugarplum with tights and brown shoes, she said, “It didn’t make sense for me to go back.” As she rose through the ranks to become principal, Anderson wore a variety of shades depending on the role: pink if she was in the body or in a work by Balanchine, tan for classical ballets, or a brown one. richer – more her true complexion – in her main roles.

Tights are just the start when companies are looking to truly honor diversity. The myriad of technical considerations for dancers of color extend to costumes, hair, makeup, and lighting. “You perfectly light the set and the costumes, you also have to light the dancers,” says Anderson. “All of my partners had to face an extra seat on them when they danced with me.”

If companies want to be inclusive, artistic teams can no longer be self-piloting. It requires seeing productions with fresh eyes, possibly reconsidering blonde wigs, certain hairstyles, and even sets (when Anderson danced Cinderella, the Houston Ballet created a new portrayal of a black mother). “As part of my artistic vision, I wanted to find a natural look for all of my dancers. Pink tights are traditional, but it was important to me that we found something natural for Lauren, ”says Ben Stevenson.

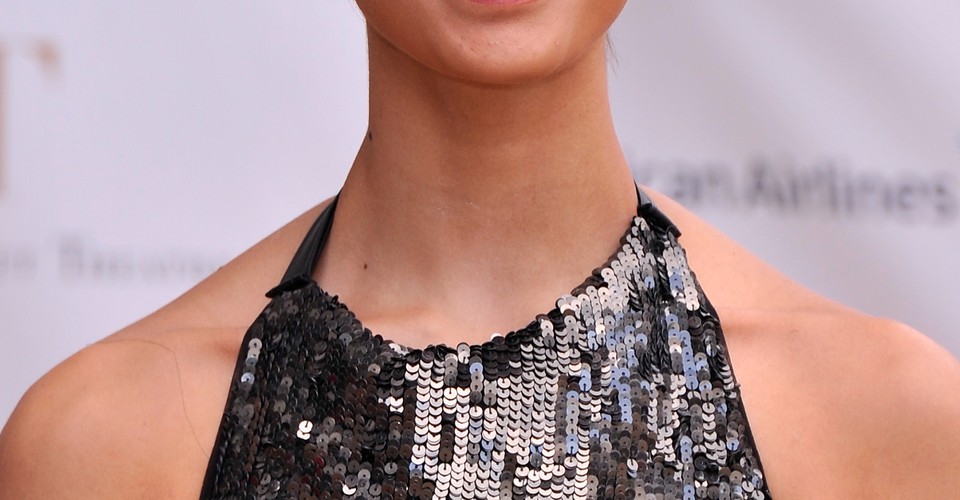

Pacific Northwest Artistic Director Peter Boal learned about the impact of open dialogue with dancers of color when he asked college student Samrawit Saleem how she wanted to wear her natural hair for the role of Clara. the Nutcracker the photo of her double-stranded twist has gone viral.

Samrawit Saleem, photo by Angela Sterling, courtesy of PNB

A by-product of inviting others is that you need to engage with them and consider their feelings and experiences. You have to ask people what would make them feel included, without assuming that you know it. It requires that you examine authentically, with empathy and compassion, the conditions under which you have functioned and that you are willing to let go of some and redesign others.

When looking for change, you can’t expect things to stay the same. When ballet organizations began their journey towards diversity, most focused only on increasing the number of brown bodies on stage. However, it is becoming clear that the issues run much deeper. Inclusion requires integration. Ballet learns that you can’t just add brown bodies, you have to change the culture. But we can start to rebuild from scratch with shoes and tights.